When the ladder disappears

Career planning in an AI world is different.

Welcome to the subscribers edition for January 2026.

Thanks again for your ongoing support. It gives me the resources needed to keep writing. As always, the subscriber chat is open if you want to send me your thoughts and feedback. I’m always listening and I would love to hear from you.

This month, we’re revisiting something I wrote several years ago before COVID-19 was even a thing: the final chapter of my first book, Become an Effective Software Engineering Manager. That chapter was called The Crystal Ball, and it presented an exercise for defining your career vision and then building a plan to get there. I still stand by this approach, and I think it’s able to unlock new ways of thinking about the future.

However, we can’t help but observe that the world, our careers, and even our industry are more uncertain than they’ve ever been. Projecting into the future is a difficult exercise, and maybe, depending on how you are feeling, even a futile one. So what should we do? Perhaps we should plan differently.

So, here’s a rework of that chapter. Instead of asking you to plan a destination, this article offers a different exercise: one that helps you define your north star: who you are, what you value, and what kind of work you want to be doing. Not titles, companies, or rungs on a ladder that may no longer exist. This is an exercise I’d highly encourage you to do for yourself, but also to do with your teams. It’s a great way to start the year together.

Here’s what we’re going to cover: we’ll start by looking backwards at how much has changed (and my, hasn’t it just?), then sit with the uncertainty that makes traditional career planning so difficult. After that, we’ll work through the exercise itself. Finally, we’ll look at how to use what you’ve created as a tool for making decisions.

I know that it’s easy to read exercises like this and think “I’ll come back to that later”; I’ve done it myself often, with many important things. But I highly recommend finding a little time to yourself at some point during your day or evening to go through this with a pen and paper. I think that it’s always valuable to introspect about what matters most.

So, if you’re ready, let’s go along for this ride together.

The backward look

Before we think about the future, let’s look at the past. Not to dwell on it, but to notice something important: a lot can happen in ten years, much, much more than you might ever have imagined. We tend to look backward and mentally compress timeframes, forgetting just how much actually happened. Think about it: ten years is longer than secondary school, and it’s the length of three university degrees, or about two and a half PhDs, and this is exciting thinking about what might change in the years to come.

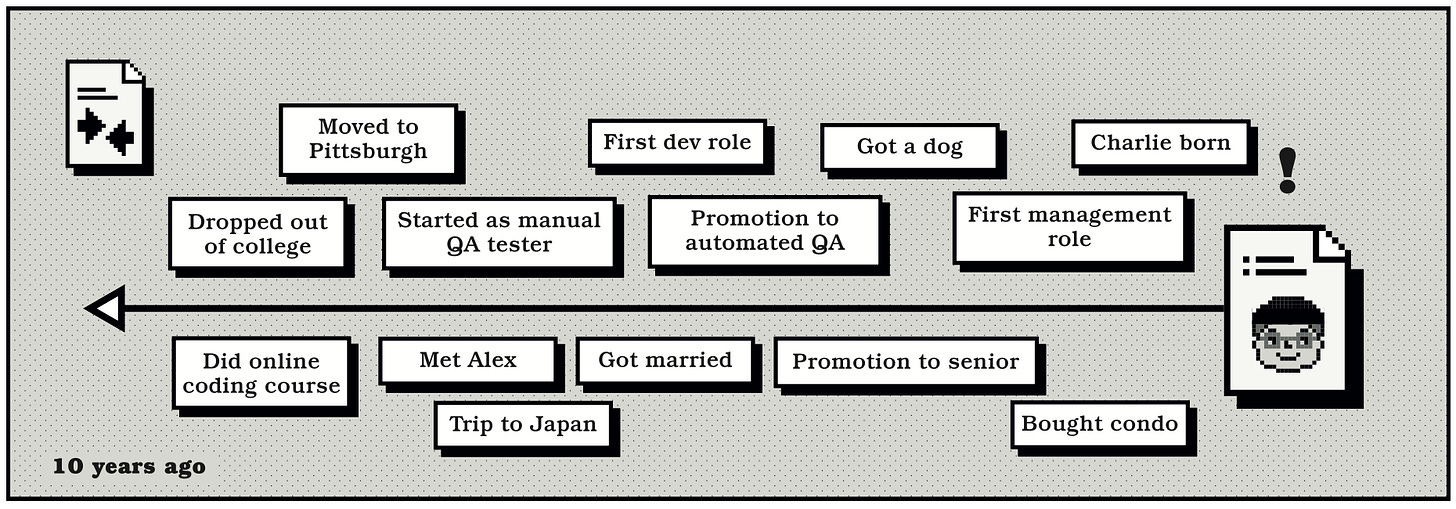

So here’s the first part of the exercise. Draw a line on a piece of paper, or open a blank document if you want to do it digitally. Mark the left end as ten years ago and the right end as today. Now plot the significant changes in your life along that line. Not just your professional life; everything. I’m talking about jobs, promotions, skills you learned, companies you joined or left, cities you moved to. But also relationships, children, losses, moves, health, adventures. Good and bad, get it all down.

Now, if you’re earlier in your career and ten years takes you back to before you started working, that’s fine. Focus on the years you’ve been in the industry, and include significant changes from your education or early life that shaped where you are now. The point isn’t the specific timeframe, it’s recognising how much can change, and how little of it you could have predicted.

Take a step back and look at what you’ve drawn. Ask yourself:

How much of this could you have predicted looking forward ten years ago?

What happened that you never saw coming?

Which events changed your trajectory the most?

What’s on the line that you’d forgotten in day-to-day life until now?

Now, let’s zoom in on the last five years, because this part of your timeline probably looks different and denser than the rest. I mean, think about everything that’s happened since 2020: a global pandemic, lockdowns, the sudden shift to remote work, followed by the hiring boom of 2021 and 2022 fuelled by zero interest rates, and then the sharp correction that brought layoffs, hiring freezes, and the flattening of organisations. And then AI: ChatGPT arriving in late 2022, and within months, tools that genuinely changed how many of us work. All of that in just five years. Wild, isn’t it?

Go back to your timeline and think about how these events mapped to your own experience. What’s changed in how you work, where you work, who you work with, and what your role actually involves day to day? Is there anything you missed? Add it now. What happened to you versus what did you make happen?

Try putting yourself back ten years in the past. What were you thinking about at the time? What did you think your future would look like? Maybe you had a plan, maybe you had ambitions, worries, expectations. Now contrast that with what you’ve just written out. How much of it matched?

Now think about this: if you couldn’t have predicted where you are now from ten years ago, or even five years ago, what does that tell you about predicting the next ten? The next five? The world you are in when you plan is never the world you’re in when you get there.

Sitting with uncertainty

So here’s the uncomfortable part: if that much changed in the last ten years, and especially the last five, what certainty can we have about what we’ll be doing in the next ten? Or the next five? As you saw in the exercise, it was hard enough to predict back then, and arguably it’s even harder now. The honest answer is: not much.

Traditional career planning assumed a relatively stable world. You could look at people five or ten years ahead of you in their careers and see a path that might be available to you. The rungs of the ladder were visible, and I’ve written about them before: the two tracks of growth, the journey from IC to manager to director to VP.

Although the titles varied, the shape of progression was familiar. You knew where you were going, even if you weren’t sure exactly how long, and at which company, but you’d get there.

That assumption is now sitting on weaker ground. There are at least three sources of uncertainty that make the old mental models harder to rely on.

AI is changing knowledge work like ours. Assuming you haven’t been hiding under a data centre for the last three years, you’ll have seen and experienced this first hand. We don’t know exactly how this will play out, but it’s reasonable to expect that some of the work you do today will be done differently, or not at all, in future. The specific skills that got you here, such as knowing a particular programming language or domain, may not be the skills that matter most going forward. This isn’t meant to be downbeat or negative; it’s just honest uncertainty.

Flattening organisations mean fewer management positions. The Great Flattening has seen companies cut management layers across the board. If you’re an individual contributor who was planning to move into management, that path is narrower than it was, and it might not even be as appealing as it once seemed. If you’re a manager who was planning to move up, there are fewer rungs above you. The old mental models may not apply.

The nature of “senior” may be changing. Here’s a hypothesis: if AI can handle more of the routine, mechanical work, then what does it mean to be senior? Perhaps increasing seniority will mean less deep programming and more managing a team of agents. Maybe the senior engineers of the future will spend their time orchestrating, reviewing, and directing AI rather than writing code themselves. We don’t know yet, but it’s worth considering given the rapid pace of change and capabilities. This may or may not make particular paths attractive.

This isn’t meant to be a pessimistic or optimistic view; in fact, only your own reaction to the direction things are taking can determine that. But what is for certain is that the path is less clear and predictable than it used to be. The destination you’re aiming for might not exist by the time you get there. So what do we do instead?