How do I get everyone to use AI?

Encourage, coerce, or force? And how do I deal with cost?

Welcome to the subscribers edition for December.

Thanks again for being a subscriber; I really appreciate it. As always, the subscriber chat is open if you want to send me your thoughts and feedback in order to shape the future of this newsletter. Message me any time. I’m always listening.

As we close out 2025, I’ve been reflecting on a question that I’ve been asked more than any other this year: “How do I get my team to actually use AI to its full potential?” It’s a question that comes up at conferences, online, and in one-to-ones with other leaders. And I get it: driving AI adoption has been a core part of my role this year.

When I started my current CTO role, I came off the back of intense accelerated AI adoption at Shopify and had been extensively experimenting with LLMs for my own work, using them as thinking partners, research assistants, and coding companions.

As part of my interview and onboarding process, there was a clear feeling that AI wasn’t being used enough in the engineering organization, and that they wanted me to come in and drive adoption to increase throughput. But the question was: how?

This initial mismatch (which is now dramatically different) became one of the most interesting leadership challenges I’ve faced. How do you drive adoption of something when you can’t force people to see its value? How do you create the conditions for playful and healthy discovery rather than mandating compliance?

Throughout 2025, we’ve seen the media report on companies taking a strong-arm approach; effectively declaring it an immediate performance issue if engineers aren’t utilizing AI tools. While that is one way to go about it, I prefer a more organic approach that I think works better for most organizations that aren’t the top 0.1% big technology companies.

If you’ve been following along with my previous articles on AI, you’ll know that I’ve written extensively about using LLMs as a leader: as a thinking tool, a co-processor for the brain, and a way to accelerate decision-making. Articles like Leadership co-processing with LLMs and Councils of agents explored these ideas in depth. If you haven’t had a chance to read these, do check them out. I think they might give you a number of ideas on how to use AI more creatively in your thinking processes.

But this article turns the attention to a different challenge: getting your engineers to use AI both at all and then efficiently and effectively. Because while I’ve been a heavy LLM user for years now, the reality is that adoption across teams is uneven, and that unevenness is costing organizations real value.

I spoke about this subject at LeadDev Berlin earlier this year. The talk went down well, provoking a number of incredibly insightful conversations with others, and I thought it deserved a long-form write-up where we could really dig into the material. If you are going into 2026 wondering how to drive AI usage in your organization, this exploration is for you.

It might be worth getting a cup of tea for this one.

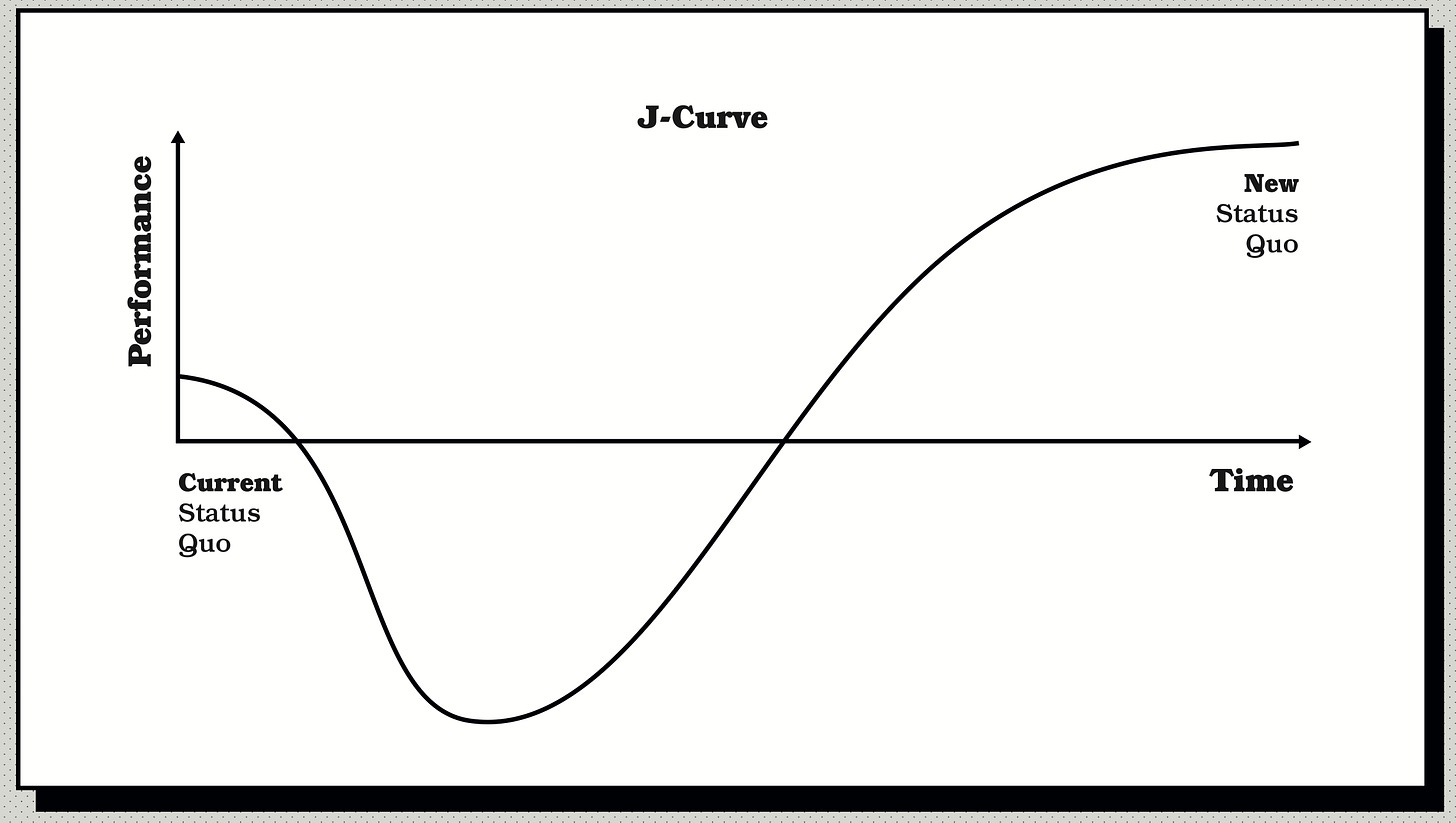

The J-curve

So, how do you get anybody to adopt anything? Before diving into tactics, I think it’s helpful to understand the shape of adoption itself. This brings me to a model that often bubbles up in my mind: the Productivity J-curve.

Humans have been through numerous productivity revolutions: the printing press, the Industrial Revolution, personal computing, the internet, and smartphones. For each of these technologies, adoption follows a J-curve.

But how do you read the J-curve? Let’s read it from left to right.

First, a new capability piques everyone’s interest. There is an initial burst of adoption and productivity as people lean hard into the phenomenon to see what it can do.

Then, reality sets in. The delta between the hype and the practical application sends the user experience into a trough of disappointment. Suddenly, it feels like using the new technology makes everything slower, worse, or more difficult. Resistance builds, and people wonder whether it was all just hype.

This trough is normal. But as time passes, as people learn the tooling and the capabilities improve, productivity begins to grow beyond the baseline, and then productivity outpaces the status quo before that technology came about.

We can pull from a number of examples from over the past decades to see how this occurs.

In 1987, Nobel laureate Robert Solow made an observation: “You can see the computer age everywhere but in the productivity statistics.” This became known as the Solow Paradox.

Despite massive investment in information technology throughout the 1970s and 1980s (computing capacity in the United States increased a hundredfold during this period) labor productivity growth actually declined, dropping from over 3% annually in the 1960s to roughly 1% in the 1980s. Businesses were buying computers, installing networks, training staff, and watching their productivity numbers go backwards.

The paradox persisted for nearly a decade. Economists debated whether computers were fundamentally unproductive, whether measurement was flawed, or whether something else was happening entirely.

Then, in the mid-1990s, everything changed. US productivity growth surged from 1.5% to 2.5% annually between 1991 and 2007. Research from the Federal Reserve later attributed roughly two-thirds of this acceleration to information technology: both the production of computers and their use across the economy.

The lag wasn’t a failure of the technology; it was the time required for organizations to fundamentally rethink their processes. Companies had to stop using computers to do old things faster and start using them to do entirely new and better things. After all, nobody needs a faster horse.

The same pattern was observed with smartphones. Whilst the iPhone launched in 2007, only 35% of US adults owned a smartphone by 2011. Early enterprise adoption was marked by fierce debate about whether these devices were productivity tools or productivity killers.

Research from the period documented a “latency effect” of approximately three years before mobile phone investments showed up in productivity statistics. Businesses had to figure out Bring Your Own Device policies, mobile-first workflows, and entirely new categories of work that simply weren’t possible before. By 2023, smartphone penetration reached 91% of US adults, and the debate about whether they were useful for work, or even useful at all, seems like ancient history.

As we have seen, the pattern is consistent: initial hype, a frustrating trough where the technology feels like more trouble than it’s worth, and then a new level of productivity and also a status quo which people couldn’t imagine not existing.

We are seeing the pattern reoccur with AI right now. At a macro level, the industry is navigating this curve. But critically, every individual in your team has their own local curve. As a leader, you must set expectations upfront: the beginning of the adoption process may feel slower, not faster. That is the investment period, and we must be mindful of this before it pays dividends. The Solow Paradox lasted nearly a decade for personal computing, and roughly three years for mobile phones.

With AI, the curve may compress: the tools are improving faster than any previous technology, but the trough is still real, and your engineers are no doubt hitting it at all points along the curve. Some may be struggling to get started, some may be finding it goes against some of their principles for what engineering is, and some may find it unwieldy and hard to keep under control.

So, with the J-curve in mind, the question becomes: how do you help people through it? It’s worth noting that some companies have decided to take a very direct approach.

The forced adoption spectrum

Not every company is willing to let the J-curve play out naturally. In 2025, we saw high-profile examples of leaders trying to accelerate adoption through extreme measures.

In April, my old CEO Tobi Lütke posted an internal memo on X after learning it was leaked. The memo declared that “reflexive AI usage is now a baseline expectation at Shopify. Teams must demonstrate why they cannot accomplish their goals using AI before requesting additional headcount.” AI usage immediately became part of performance reviews. Prototyping, Lütke wrote, should be “dominated” by AI exploration. “Stagnation is slow-motion failure,” he warned.

A few months later, Coinbase CEO Brian Armstrong took an even more direct approach. After purchasing enterprise licenses for GitHub Copilot and Cursor, he posted a mandate in the main engineering Slack channel: onboard to AI tools by the end of the week, or attend a Saturday meeting to explain why. Those who showed up without a good reason were fired. “I went rogue,” Armstrong admitted. “Some people really didn’t like it..., but, as you know, I think it did set some clarity.”

So, if you’re Shopify or Coinbase, i.e. companies with global fame where engineers line up to work regardless of culture, you can make these moves, if that is how you wish to run your company. The talent cost of an extreme mandate is lower when you can backfill quickly with people who want to be there. Your brand kind of absorbs the reputational hit.

But, as you know, that’s perhaps 1%, maybe less, of companies out there. For everyone else, forcing adoption risks resentment, shadow non-compliance, and losing good people who feel micromanaged rather than empowered. The engineers who leave first are often the ones with options, who are also your best performers.

So where should you position yourself?

Let’s look at how to tackle culture and also crunch some numbers so you can convince Finance.