How do I get better at giving feedback?

A model, a process and a habit.

This week, we’ll look closer at a subject that seems simple in principle, but in practice can be quite tricky.

Q: How do I get better at giving feedback?

I’m aware that the topic of giving feedback may come across as quite dry, and that the next tab or email might appear more interesting to read; but please be patient with me here. It’s worth it.

Being able to frequently give and receive feedback—especially feedback that is clear, concise and actionable—can completely transform your relationship with your colleagues.

It works wonders in all job roles.

If you’re a manager, it can make you far more effective at running your team and coaching your direct reports. If you’re an individual contributor, you can concurrently build high trust with your peers and also ensure that the quality of the work and the interactions that you’re having are always trending in an upward direction.

All of this is possible through the simple process of giving frequent, good feedback.

However, I know as well as you that giving feedback is hard. It can often feel awkward, forced, and worst of all, insincere—even if you don’t intend it to! Sometimes you don’t even feel like you’re the kind of person who’s good at giving feedback—or even allowed to do it—so you shy away from it.

But, with continued practice, you can build the confidence to make it as common in your daily routine as having lunch, and your colleagues will thank you for it.

Let’s explore feedback in three important ways, calling upon some excellent ideas.

We’ll look at:

A model which will help you ensure that the feedback you’re giving is of high quality.

A process for giving feedback which is short, simple and repeatable.

A habit which will help you embed feedback into more of your interactions, helping you get better at giving it, and also will enable a culture of bidirectional feedback with others.

We’ll begin by looking at a model from one of the best books out there on the subject.

A model: Radical Candor

It seems that some of the best models that we call upon are arranged as quadrants.

The Eisenhower decision matrix has helped me greatly in organising my personal priorities, and the effort versus impact matrix has helped many of the teams I have been part of over the years think about which tasks to tackle first.

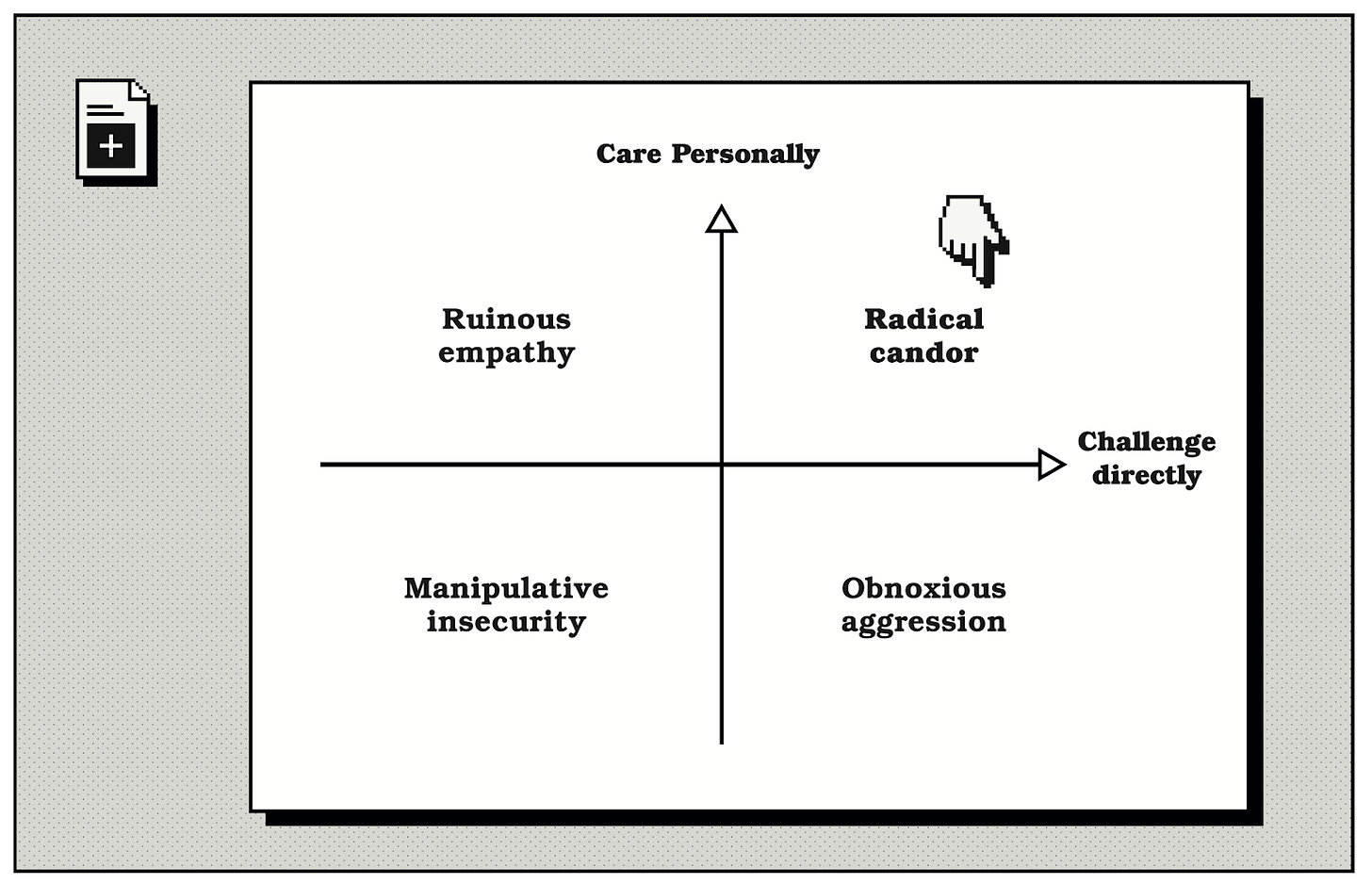

There’s another excellent quadrant model that reshaped how I think about giving better quality feedback to people, and it comes from Kim Scott’s wonderful book Radical Candor.

Scott considers the two most important parts of giving feedback are that you must:

Care personally about the person that you’re giving feedback to, and that you must also

Challenge them directly by being clear and to the point.

When you are doing both of these things, then you are exhibiting radical candor. It’s radical because so few people are good at doing it!

What’s even more interesting is that when you visualise these two characteristics with a quadrant, it also highlights the pitfalls that we face if we only do one (or none!) of them.

Here’s what it looks like:

So what do these words mean in the quadrants? Let’s step through them:

Radical candor is what happens when you care personally and challenge someone directly. You say what you think and deliver the feedback precisely but in such a way that ensures the recipient sees that you are doing so because you care. This is where you want to be. It promotes trust and growth. But, as we all know, this takes practice.

Ruinous empathy happens when you care but don’t challenge directly. It’s either unspecific praise or diluted criticism to avoid a difficult message. This doesn’t help the recipient improve. So many new managers fall into this trap where they are afraid to say what they think because of the fear that it will cause conflict. The irony is that it’s worse for the recipient, who doesn’t know that they need to improve.

Obnoxious aggression is when you challenge but don’t care. It’s insincere praise or mean criticism. Insert your stereotypical hot-headed male executive here.

Manipulative insincerity is when you do neither. Good behaviours go unpraised, and bad behaviours are ignored. As a leader, this is a complete dereliction of duty.

Can you think of situations that you’ve witnessed in your own life that fall into the categories above? Perhaps you worked with a colleague who was performing badly and was a burden on the team. It may have been because your manager was demonstrating ruinous empathy by never tackling the performance problem directly.

Conversely, you may have witnessed a manager who seemingly never praised their team and would get angry and overly personal in their criticism. Would you place them in the obnoxious aggression category?

Remember, whenever you give feedback, you want to be radically candid. Not only does it make you better at giving feedback, it’s essential for ensuring that those that you work with are able to improve and get better.

Feedback is a gift.

A process that works every time

Even if you’ve fully understood radical candor, feedback is like writing, programming and exercise: you don’t get better by reading about it. You get better by doing it.

The only issue is that because communication can be messy and also humans can be unpredictable, we can have many bad experiences that make us hesitant to keep training our constructive criticism muscles.

Ideally, what we want is a clear process that we can follow every time that takes a lot of the work out of delivery. We often know what we want to say, but struggle to say it in an optimal manner.

Enter LeeAnn Renninger, who has a fantastic short video on a proven method for giving effective feedback.

The process breaks down giving feedback into four stages:

Start with a micro-yes. Getting unexpected feedback out of nowhere can be unsettling for many people, so the first step involves getting the recipient into an open mindset about receiving the feedback. This is a “micro buy-in” and can be a simple question: “I’ve got a couple of ideas for how we could improve. Can I share them with you?”

State your data point. Next, you should be specific about what you’ve observed, using as much data as possible. For example, “we said we’d ship this change by midday, but it’s now 4PM” or “this proposal is currently too technical for our stakeholders to understand”.

Make your impact statement. Following the data point, you state what the impact of the data is. For example, “our support staff are getting inundated with tickets because we said that it would be fixed earlier”, or “this will make it highly likely that we won’t get buy-in for our project”.

End on a question. This opens the floor for the recipient to start discussing the feedback with you. For example, you could say “what are your thoughts about that?” or “how do you see the situation?”. You’re actually asking for feedback on your own feedback!

Try it out. Start using this model in your feedback next week and see whether you feel more confident and impactful in what you are saying. It definitely helps me organise my thoughts and ensure that they aren’t accidentally going to land in a confrontational way.

You could even share the video above with your team and spend some time roleplaying some situations with them. You could imagine some scenarios, and then pair up and take turns at applying the feedback model.

For example:

Roleplay 1: One person is the manager delivering the feedback and the other is the direct report. The direct report has been off sick for two days but did not contact the team at all to tell them where they are. The manager wants to tell them that this isn’t acceptable.

Roleplay 2: Both people are individual contributors and one of them has been up all night on-call because of a production issue. It turns out that the issue was caused by a change that the second person pushed straight to production without getting a pull request review at the end of the previous day. They need to be told that this isn’t a good way of shipping code.

Roleplay 3: One person is the direct report delivering the feedback and the other is the manager. The manager recently exhibited obnoxious aggression in a meeting when the team’s priorities were rightly challenged, and the team feels deflated and upset as a result. The direct report wants to tell the manager they didn’t act as a leader in that meeting.

I’m sure you can invent plenty of scenarios to practice on as well. If you find it hard to get buy-in to do some roleplaying in your team, why not give them some feedback on why it could be beneficial?

A habit: sharpening your tools

Like fitness, if you don’t keep practising, your performance will decline.

In order to get good at giving feedback you’ll need to ensure that you’re doing it all the time. I’m talking daily.

The reason that giving feedback can be so hard is that so many of us associate the term “giving feedback” with “giving bad feedback”. In all likelihood, your colleagues are probably doing many things every day that deserve good feedback, including you.

As a rule of thumb, I find that nine out of ten pieces of feedback I give are always positive if I’m actively looking out for the opportunities to give them. This gives you a great opportunity to form a virtuous feedback cycle that acts as a flywheel going forwards.

By seizing feedback opportunities, you can do the following:

Practice radical candor. Remember that you want to care personally and challenge directly. You can always gain comfort and confidence by leaning strongly into the caring element. If you truly care, then the only motive that you have for giving feedback is for the other person to improve. So be sincere, and the rest will follow.

Practice the feedback process. Once you’ve shaped what you want to say, follow the four steps above. Open with a micro-yes, share your data point, make your impact statement and then end on a question. With time, you’ll be able to do this automatically without thinking.

Feel confident in your feedback skills. As time goes on, and with each piece of feedback that you give, you’ll have positive experiences that can feel like real personal breakthroughs with others. This helps form a virtuous cycle that will make you want to give feedback more often.

Be seen as someone who others expect feedback from. I once worked with someone who was so consistent at giving feedback that I knew as soon as I gave a presentation to a group, or circulated a document, I’d receive a message outlining what they thought about it. It was great: I always felt that this individual was looking out for me and I could trust them to call out if there was something that I could do better next time. You can be that person.

Ensure that you’re a well-oiled feedback machine for when you need to deliver critique. Practising positive feedback daily benefits you in two ways: not only does it make you better at doing it, it also builds trust between you and the recipients. This trust can then be leveraged when you need to occasionally give critique. It makes it so much easier to deliver.

So go on: start right away. With time, what comes naturally to you will be seen as a superpower to others. All it takes is a little practice.

Further reading

If you want to dive deeper into giving feedback, then there’s a number of books that I recommend:

Radical Candor is highly recommended, and it’s where the model presented earlier on is taken from.

Crucial Conversations is worth a read if you’d like to delve deeper into how to handle high-stakes situations whilst ensuring that you get the results you want.

And of course, we explore feedback and communication in many situations in depth in my first book Become An Effective Software Engineering Manager, and we go deeper into communication in my second book Effective Remote Work. Picking up a copy of one of my books is the best way to support my writing.

Do you have any stories of when feedback has had a profound effect on you—good or bad? I’d love to hear from you.