How do I deal with my manager changing?

The inevitable, handoffs, and contracting.

If there’s one thing as sure as death and taxes, it’s the fact that you’re going to have many managers over the course of your career. Even if you stay at the same company for decades, it’s unlikely that your manager is going to as well.

What’s more likely is that you may find yourself with a new manager every few years, due to one or more of the following reasons:

You change jobs.

You move to another team, either by choice or because priorities have changed.

Your manager leaves.

Your manager moves to another team, for the same reasons as above. You get the picture.

So, this week, we’ll look at the following question:

Q: How do I deal with my manager changing?

Change isn’t all bad

I think it’s important to begin by addressing the elephant in the room: changing managers shouldn’t be avoided at all costs.

In fact, it can be good for you. Sometimes getting too comfortable under someone can hold your development back, compared to someone that could push you outside of your comfort zone, help you work on something new, and make you see sides of yourself that you hadn’t been made aware of before.

If you really want to work on something different, but you pass because it means changing managers, then you’ll eventually regret missing that opportunity just for keeping the familiarity of your current relationship.

However, the reason that people avoid changing is completely understandable: we’ve all had our share of experiences with our managers, from the good to the bad. Reporting to a good manager is a joy. And when you’re reporting into a bad manager, work can really suck. So why take that risk?

After all, your manager is responsible for your performance reviews, finding opportunities for you to grow and progress, and for making sure that you’re happy and productive day to day, week to week.

Even if you try your best to stay with the same manager, much is outside of your control. They may leave. You might get moved to another team. So, with time, it only becomes more likely that you’ll be reporting to someone else.

Therefore the question remains: how can you get things off on the right foot when you make the switch?

We’ll break this into three different parts that represent the past, present and future at the point of changing. But first, let’s look at some general advice.

Own your own development: push, don’t pull

Actors in a system can only affect what they can fully control. Everything else is up to the altruism of others or just pure luck. This holds for your career as well.

If you give complete control of your growth to your manager, then you may get lucky with someone that truly dedicates their time and attention into finding opportunities for you, lays out clear goals for you to reach, and ensures that you’re always progressing at all costs. However, the likelihood that you’re going to find a manager that does this consistently is low.

Why? Well, not only does it take a huge amount of time for any manager to plan development for each of their direct reports, fundamentally you are the one that best knows yourself and where you want to go, not your manager.

Instead of seeing your manager as the pilot and yourself as the passenger, you need to work that relationship differently with yourself as the pilot and your manager as the copilot.

You need to know where you want to go, and you need to steer in that direction with their help.

Think about it: if you were managing someone and they were able to take the lead on suggesting their goals, asking you for more work, and encouraging you to delegate things to them, wouldn’t that be wonderful?

Being proactive with your development ensures that you get what you want since you know yourself best, and it makes your manager’s life easier because they can be the copilot, rather than the pilot. Yes, you can ask for advice. But you take control of planning your direction of travel.

And, if you have managers that you don’t really gel with—as we all have had in the past and will in the future—then having them occupy a position where you can set the direction and then mostly get out of your way can be liberating for both of you.

So always own your own development and push towards it, rather than waiting for your manager to find you opportunities and to pull you along. The latter rarely ever yields optimal results.

The past: the handoff and your audit trail

Let’s now look at the switching point.

When you change managers, they won’t know your past. They might have access to your previous performance reviews, but they weren’t written by you, nor do they represent your whole self.

What can you do?

If you can, try to arrange a manager handoff with your previous manager and your new manager. This is a 1:1:1 (read: one-to-one-to-one) where all of the important information is passed from your old manager to your new manager whilst you are there.

This is important because that transfer is transparent to you, ensuring that you have the opportunity to know that it’s happened, can hear what is being said and therefore reduce the friction in the process.

The agenda of the meeting is as follows, mostly driven by the former manager:

Details from your most recent review cycle.

Your recent feedback, current projects and other relevant information.

Your goals, growth areas and any important things for the new manager to know.

Read Lara Hogan’s post in detail to see exactly how to structure the meeting and ensure that all parties leave satisfied.

Also, in the spirit of pushing, rather than pulling, we wrote last week about how you can ensure that your work is visible. Check it out if you haven’t already.

The core of the practice is creating a habit of writing “brag docs” at regular intervals—say, weekly or fortnightly—that detail everything that you’ve been working on, from the tangible (e.g. shipping a feature) to the less tangible (e.g. that you made a decision, or mentored a colleague).

If you get into the habit of writing these and sharing them with your manager, then the archive can come along with you when you switch, giving your new manager the ability to read through what you’ve been up to for the last weeks, months, and years if they wish.

By lining up a manager handoff, and by having a past audit trail of your work as written by you, not only have you given your new manager plenty of opportunities and material to understand where you’ve been and where you want to go, you’ve also been present and have had complete control of the process and information.

The present: contracting

Now, let’s move on to the present. You’ve had your manager handoff and you’re about to have your first one-to-one meeting. What do you do?

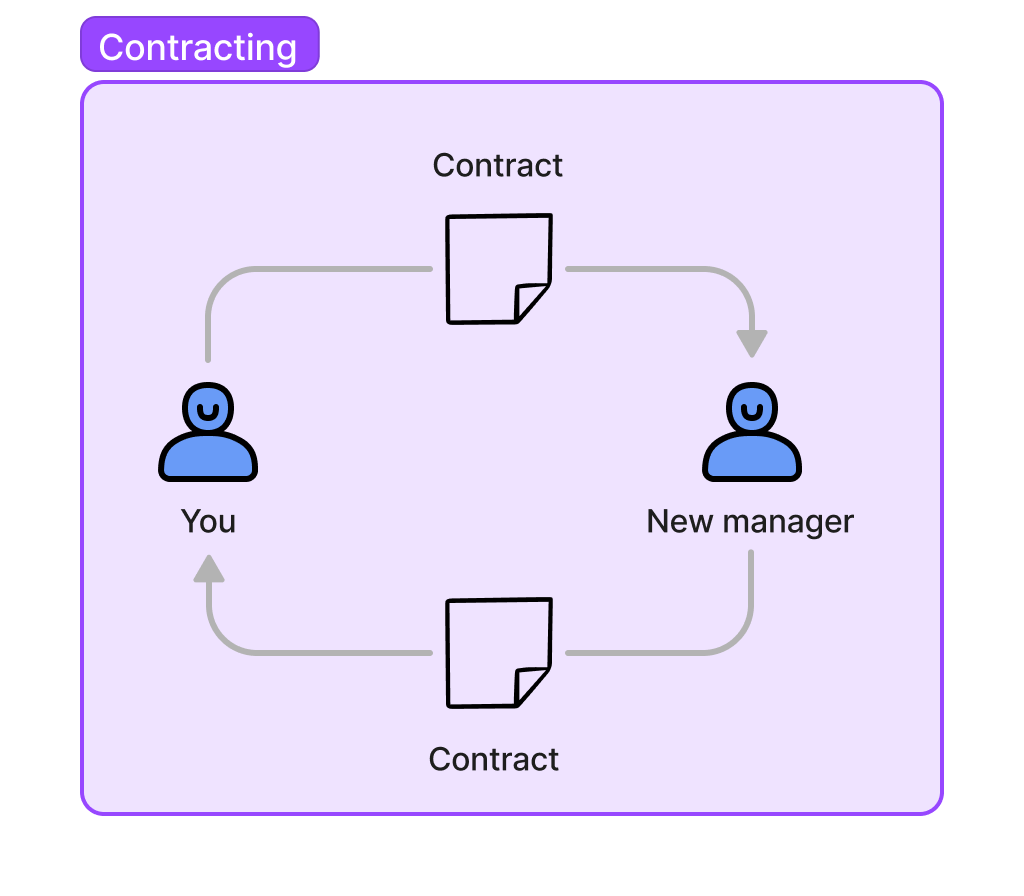

I always recommend an exercise called contracting, which I learned a long time ago from a workshop with Conscious Business People in my early management days.

The idea is that you’re starting a brand new relationship and your first meeting together is an opportunity for both you and your new manager to make it really clear as to what you both need from each other in the relationship.

The contracting exercise is just a few simple questions that you prepare beforehand. You then come to the meeting to talk through your answers with each other and to discuss how you feel about them.

The questions are as follows. They’re two-way, as a direct report supports a manager by helping their team succeed.

What are the areas that you’d like my support with? This can range from technical challenges, performance management, visibility into other areas of the company, and so on.

How would you like to receive feedback and support from me? This is about working out how the other person likes to operate. Do they prefer written or verbal feedback? Do they prefer synchronous or asynchronous communication? Everyone’s personalities and preferences are different, so this gives an opportunity to uncover that.

What could be a challenge in us working together? As before, everyone’s personalities and preferences are different, so that can cause some clashes, and these can be explored. Additionally, are there big skill set gaps that might make the relationship harder because one person doesn’t have in-depth knowledge of the other’s world and vice versa?

How might we know if the support I’m offering isn’t going well? If there are occasional flashpoints, or if the relationship really starts to go downhill, how will both parties know? Do they feel comfortable just saying so, or are there particular behavioural signs that each other can look out for such as quietness, frustration, or lack of responses to messages?

How confidential is the content of our meetings? Since one-to-ones are private, sensitive topics can arise. Should those topics stay completely private, or are there circumstances where that information could generate some actions? If so, how should permission be granted to share private information if it needs acting upon?

Contracting is a great exercise to get relationships off on the right foot, and it doesn’t have to be used exclusively between managers and direct reports. It works between any two people. It’s also a neat tool that you can use to reset relationships as time and circumstances change them.

The future: your goals

With the relationship with your new manager grounded, you should also take ownership of coming up with your goals and trying to achieve them. I’ve always been a big fan of the 30-60-90 day plan when moving into a new role, but it also works really well when starting out with a new manager.

The reason is that when you start with a new manager, you want to build two-way confidence in that relationship from the start to show that you’re someone that they can rely upon to get your job done.

By starting with this short time frame of three months with a check-in every month, you get plenty of opportunity to start building a goal-centric relationship with your manager, which will frame the rest of the relationship that you have with them.

Doing so is simple: you just come up with some objectives to achieve within each of those time periods. The goals themselves don’t need to be ostentatious: they should just be your usual job, and the kinds of things that you’d be writing about in your brag documents.

However, you’ll find that by being able to show your new manager that you’re actively planning and achieving, they’ll more quickly give you autonomy and think of stretchier and more interesting goals that you can achieve.

Resets are good

With these tools, changing managers can be a great opportunity for a reset and a chance to shape a future relationship exactly how you want it.

You can use a manager handoff accompanied by your brag docs to cover the past, contracting to cover the present, and a 30-60-90 day plan to move you into the future.

Even if you’re not changing managers, why not give these tools a go as a way of rebooting your current relationship? Try it out.

If this article was right up your street, then there’s plenty more ideas and tools in my book, Become an Effective Software Engineering Manager.

Until next time.