Don't make yourself redundant

This article is part of a series on managing managers.

I was flicking through my dusty copy of High Output Management recently and I was reminded of this fantastic piece of advice. On reflection, I’ve realized that I’ve been using this approach without explicitly remembering where I learned about it, so it was pleasant to be reminded of its provenance.

A common route for a manager to become a manager of managers is through rapid growth in the size of a company. This can happen because of venture capital investment, through mergers or acquisitions, or, if you're lucky, through good old organic growth.

During these periods of time, more engineers get hired into existing teams in order to get things moving faster. However, there's a limit to the number of direct reports that any given manager can reliably have, and the rule of thumb is usually around 5-8, depending on who you ask, and on the preferences of the person doing the managing. When thinking about the limit, you can sometimes replace a direct report with a major initiative, such as being part of a project, guild or committee, if you're thinking about how to balance your effort between individual contribution and people management.

Splitting the atom

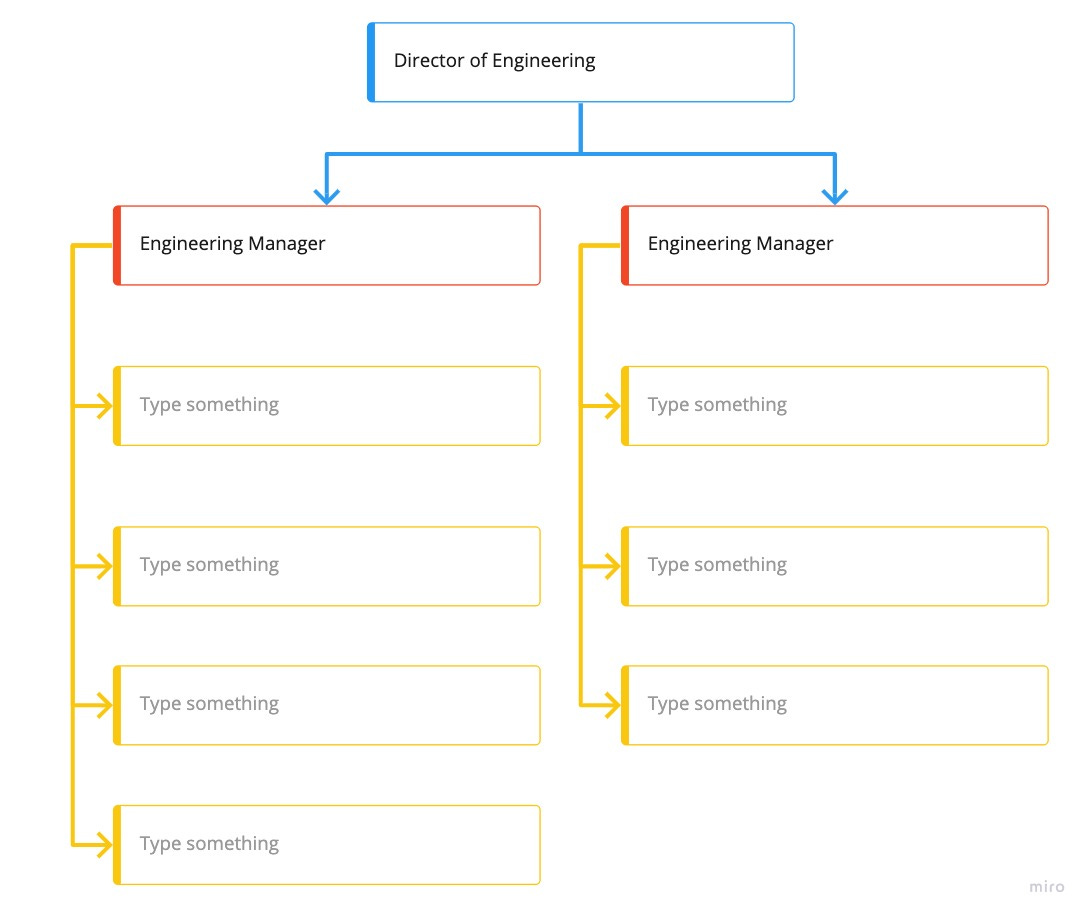

So, what tends to happen when a manager starts to get too many direct reports? Well, the answer is usually quite straightforward: try to split the team in order to create two smaller teams. That makes a lot of sense. So what might happen next? Well, our manager could create two smaller teams and promote or hire two new Engineering Managers (EMs) to run those teams, reporting to them. It might look something like this.

But wait! This is actually quite bad. Why?

Our new Director of Engineering has made themselves redundant. By going from managing too many people to just 2, they've delegated all of their responsibility without the existence of other impactful activities that they can fill their time with. They’ve entered on the job retirement. It's not a good place to be in, especially in the future if there are cuts or redundancies on horizon.

They have no way of getting involved with their teams effectively. Either they're going to have to work very closely with the teams - which would be meddling, since they already have EMs running those teams - or they're going to have to stay quite far away, which means that they can't have much impact other than coaching the two EMs.

Assuming growth doesn't continue indefinitely, our Director of Engineering is going to find themselves bored, frustrated or leaving the company - or even all three! What can they do?

A better solution

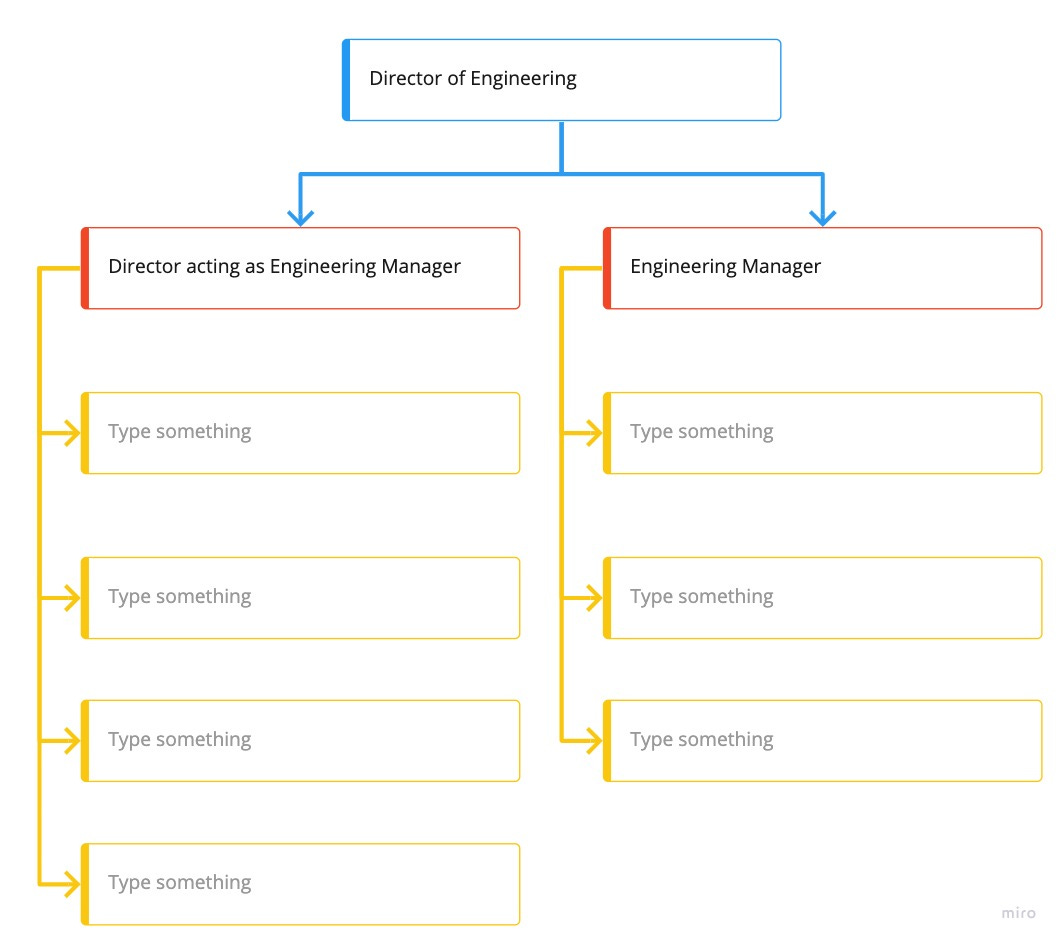

In order to not make themselves redundant, the manager that is splitting the team should instead promote or hire one EM to run one of the sub-teams, then run the other team themselves by acting as the EM even though they've moved up into a Director of Engineering role. That would look something like this.

This is much better! What it means is:

The Director of Engineering still has enough direct reports to remain productive and impactful. In the example above, assuming the new EM was promoted, they've gone from 9 direct reports to 5 - from around the maximum to the minimum - whilst still having the responsibility of running one team themselves.

By acting as an Engineering Manager, it doesn't cause imbalance in the org chart. By representing the role as “acting as”, the org chart looks like two teams reporting to two EMs, rather than one team being demoted a layer beneath another one. This keeps everyone happy.

Our new manager of managers only has to ramp up one new manager at a time, rather than two. It's hard enough to do just one, after all. This means that the right time and energy can be devoted to the task, whilst giving one of the teams their familiar, existing manager.

Although this approach may seem like common sense, it's surprising just how many times you see the initial, bad pattern happening in growing organizations. It introduces way too much change at once, resulting in too many new managers needing to learn the ropes at a given time and thus disrupting multiple teams, and encourages bad managerial behaviours such as meddling and on the job retirement. The latter is most worrisome, since your emerging leader may begin pushing themselves out of the organization.

By adopting the second pattern instead, you get smoother transitions during growth phases and better retention of momentum when teams split, and most importantly, if you're the manager doing the splitting, you stay needed, impactful and productive.