Deltas to the Global Maxima

Better conversations beyond the career track

As you likely already know, a key part of our role as engineering managers and leaders is to invest in the long term growth of our teams. In a previous article, we looked at how you should expect to push the improvement of your organization over time: you all learn, gain skills, and level up, both individually and collectively.

The resulting effect is a rising tide of organizational capability, or to borrow the name of a videogame mechanic, a power curve that should always be trending upwards: this year's organization should be far more capable than last year's. Everyone should be getting better as an expected part of their job. Staying the same is not good performance, it is stagnation.

Career Tracks: The Best of Intentions

As people follow the organization's power curve, they progress in their roles and responsibilities. In order to bring order, fairness and uniformity to this progression, good organizations provide their staff with career tracks and progression paths. These are a matrix of expectations and capabilities that a member of staff maps to at a given moment in time. By looking at the matrix, they can see where they are, where they are going, and what they need to do to get there. Going up the career track is a sign of growth and development and typically comes with increased compensation and responsibility.

If you don't have career tracks at your organization, then you can find lots of examples for inspiration on progression.fyi. Legend says that the ones that I wrote for my previous company are still on there.

Career tracks are a great compass for people to navigate their progression. For example, it should be clear at which level of seniority a staff member gains the option to choose whether or not they want to make the transition to management. Typically this happens somewhere around the Senior Engineer or Staff Engineer level depending on the organization. It should also be clear when they should be expected to be the technical lead of complex projects, or to work across multiple teams, or to be the technical authority in a given domain.

However, career tracks are tools and not prescriptions. Not everyone's progression is the same nor can that progression be distilled into linear checkboxes. And like many tools, they can be misused. In the hands of an inexperienced manager, they can become a crutch, encourage shortcuts and box-checking, and discourage long term thinking.

At best, career help staff know where they can go at a given company and provide some indicators of how they might get there. They help start a conversation. But, at worst, they can oversimplify and overgamify true growth and development, and contribute to increasing the disappointment frontier between staff and their managers.

Oversimplifications and Random Walks

So why is it that career tracks can be misused? The issue is that they are a simplification of a complex, multi-dimensional problem space. People's careers can go in limitless directions, and career tracks are just one possible path at one possible company. They are represent a local maxima, not the global maxima.

People are different. One person may seek to run increasingly larger teams and organizations, continually pushing themselves outside their comfort zone, whilst another may thrive by running one team whilst still contributing technically, enabling them to continue to hone their craft.

Another person may want to stay at a certain level of technical contribution (e.g. Senior Engineer), but experience many different companies and problem domains over the years. Variety is important for them. Another may want to become a specialist and work on a single problem for their entire career; perhaps even at the same company. Here, depth is key.

Our final hypothetical person may just want to just make enough money, in whatever means possible, so they can stop working full time and concentrate more on their true hobbies and passions. Here, the end goal is not even career progression, but maximizing their gains toward financial independence.

Each of these people will want to walk different paths, and each of these paths will be unique to them.

Given that career tracks represent a local maxima of a single company and not the enumeration of the possibilities of an entire career, the problem hampering many manager-report relationships is that all coaching and personal development focus is limited to the next step on the ladder at the current company, and nothing beyond that.

Now, there is some good that can be attributed to a limited focus:

The next step on the career track is the most immediate and tangible goal, which means it is the easiest to make an actionable plan for.

No manager wants to lose a good report, so they will naturally gain by overindexing on pushing the next step at the current company.

Coaching people toward the bigger picture is hard, and requires a great deal of skill, time, and acceptance that their future may be in a different team or company altogether.

However, it can also lead to a number of problems:

If the next step is not available (e.g. there are no new teams for a budding manager to manage) then the report can become disillusioned. Despite increasing their skills and capabilities, they are not able to progress.

If the a company's career ladder does not reflect an individual's personal career goals, or does not present compelling nonlinear options, then the report may feel like they will limit their career growth regardless by staying at the company.

If career track levels directly map to compensation, then some companies may penalize those that rather wish to go deep or wide in their careers, rather than up. See the previous article on the Tarzan method for more on this.

So the question is: what do we do as managers in order to help our reports grow in a way that is meaningful to them, and not just to the company?

The Global Maxima

When we talk about career progression with our staff, we need to look beyond the career track and understand their unique longterm goals, desires, and motivations.

We need to stop obsessing over dangling the next step on the career track as a carrot. Doing so almost always leads to disappointment. Long term conversations become short term: why can't I have that role now? When can I get that role? What's the fastest way to get there? These are all questions that are focused on shortcuts and checking boxes, and not on doing impactful work for customers or increasing their skills.

Instead, we need to help our reports consider the bigger picture: what is the global maxima of their career?

This global maxima is the point at which we are at our most skilled, our most impactful, and the most satisfied. The global maxima may not even be a role, but a state of being where everything comes together: life, work, compensation, contribution, and happiness.

Try restarting your career conversations with your direct reports by asking them what this global maxima is for them.

Here are some primer questions. Try to get them to answer them in as much detail as possible, even down to where they're waking up in the morning, what they're looking at out of the window, and maybe what they're eating for breakfast (toast is good):

If you think of yourself in the future as your most successful, happy or impactful, what exactly are you doing day to day?

Where are you doing it?

What are the skills that you have that make you so successful?

What are the problems that you are solving that make you so impactful?

What are the conditions that you are working in that make you so happy?

What are you doing outside of work that makes you fulfilled?

There are plenty of other questions that you could add to this: feel free to riff on them.

Now, it can be hard to answer these questions on the spot, so maybe you could give these questions as homework at the end of a one-on-one to think about before the next one.

In order to wrap some structure around this vision of the future, you'll need to use a model. One potential model to use when doing this is of scope and impact which we previously covered.

Scope is the breadth of your responsibility. It covers the size of the team that you manage, the size of the budget that you control, the number of projects that you are responsible for, and the number of people that you influence. It is the size of the sandbox that you play in.

Impact is the depth of your responsibility. It covers the result of the work that you produce, the output of your team, and the effectiveness of the decisions that you make. It is the quality of the sandcastles that you build.

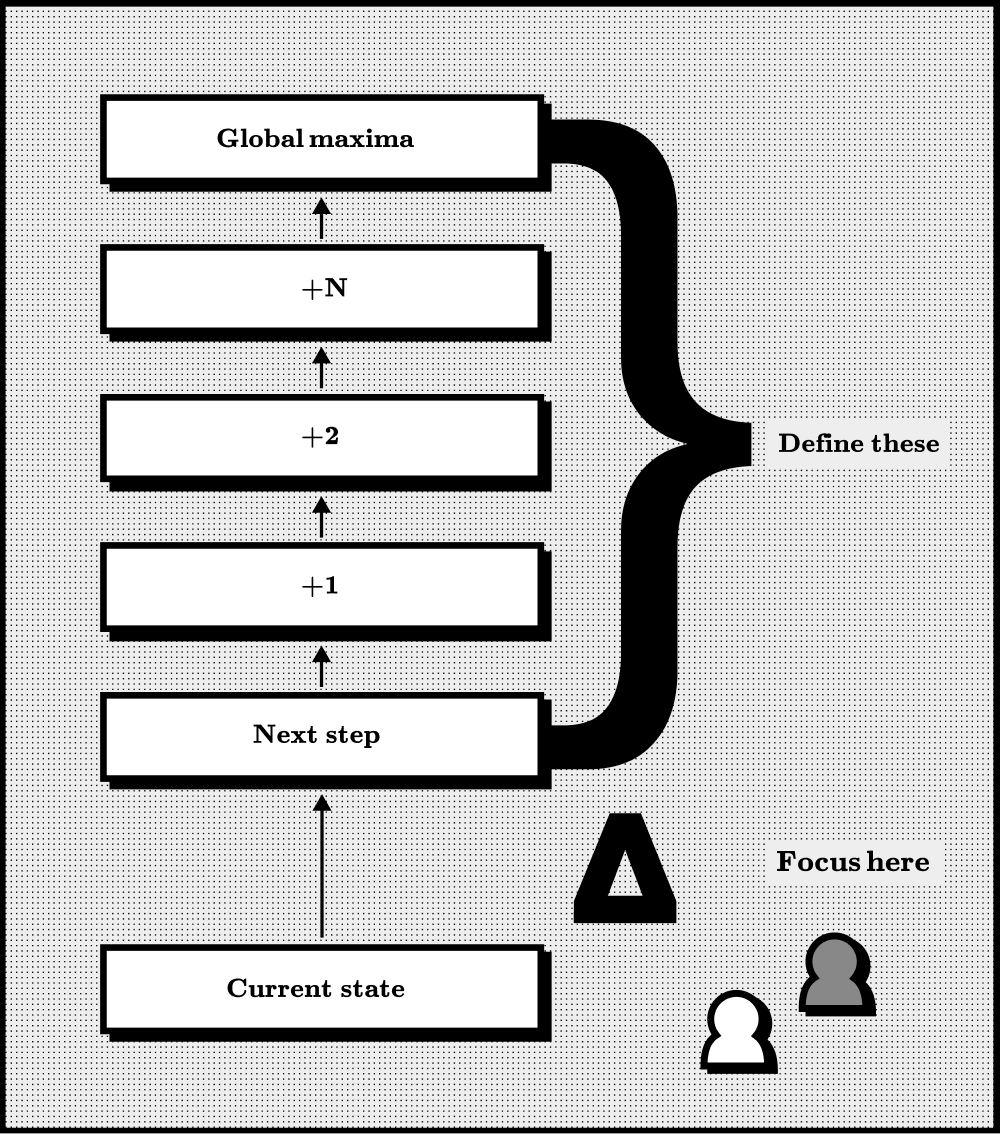

Working backward from the global maxima, start defining scope and impact for each of the steps that you defined, and then calculate the delta between each of them. This should form a rough path that they may need to follow, which may be at the current company, or it may require future journeys at many others.

For example, if they want to be a VP Engineering at a top 5 technology company, what is the scope and impact of that role (e.g. organization size, projects, domain, budget, number of reports, etc.) and then what is the difference between the scope and impact of their current role? Subtract one from the other to see the gap.

It may be that the delta is vast (e.g. they want to run a 1000-person organization, but are currently running a 10-person team). If so, that initial delta will need breaking into incremental steps of career progression until they have a series of hypothetical roles that they could take that would get them to the global maxima.

For example, imagine you and your report are at a Series A company that is fundraising. This journey might involve:

Continuing to ride the wave of growth at your current company, and coaching them so they can take on their first manager of managers role after the next round of funding opens up a significant number of new teams.

Working with them to push them as far as you can within this new role, ensuring that they are able to experience as much of the scope and impact of future roles as possible.

If growth stagnates, helping them to use this experience as a springboard to work at a top technology even if it means taking a step back in terms of title and team size.

Performing well and seeking out opportunities to increase their scope and impact at the new company. Then, repeating these final two steps until they reach their global maxima.

With the delta defined between their current state and the next hypothetical step, you can get to work on identifying possible projects, roles, and skills that can be developed to close that gap.

What is possible in the current team, role and company?

What is impossible and must be achieved elsewhere?

How can you help them at least achieve what is maximally possible at your current company (think of defining a tour of duty, for example)?

How can you help them identify where the next vine swing in the Tarzan method might lie for them? This will also help with identifying and coaching their successors.

If you can work with your staff on decreasing the delta between where they are and where they want to go, then you are going far beyond the myopic focus on the next step on the career ladder. You are helping your staff to grow into the person that they want to be, and to develop the skills that they need to get there. It builds more trust, makes career conversations more meaningful and interesting for both of you, and whether your staff stay with you in the long term or not, they will be grateful for the time that you spent with them.

You are no longer the controller of a single step; you are a guide to a whole new world of possibilities.

Have a think about it. What's your global career maxima? What are you doing this year to ensure you get there?